Chinese (Cantonese) Ginger Vinegar With Pig Feet And Eggs

Contributed by Wendy Mak, Isabella Chan and Yong Nuan Han

INSTRUCTIONS

1. Combine the 2 types of vinegar in large clay pot.

2. Prepare ginger:

scrape away skin with spoon or butter knife

divide ginger into large pieces

cut each large piece into halves

pound each half with cleaver or rubber mallet

roast ginger halves in small portion in dry wok over high heat for 1-2 minutes, stirring constantly.

3. Add prepared ginger to vinegar in pot, bring to boil, then simmer for about 2 hrs until vinegar is thoroughly seeped into ginger. Ginger-vinegar concoction can be stored in clay pot at room temperature for weeks with weekly boiling.

4. Prepare pig feet one week prior to serving.

INGREDIENTS

(40 servings, to be shared with relatives and friends)

10 pounds ginger

1 bottle (3.6 L) sweetened black vinegar

1.8 L black glutinous rice vinegar

10 pounds pig feet

40 organic eggs

5. Prepare pig feet:

heat water to almost boiling, meanwhile

clean and rid pig feet of hair;

cut into 2” x 3” pieces,

blanch in hot water, not boiling

take out immediately after stirring several rounds

rinse with water.

6. Add prepared pig feet to ginger-vinegar concoction, bring to boiling then medium low heat for 1/2 hour. Concoction of ginger-vinegar-pig feet can be kept in room temperature with boiling every 3 days. Occasional reboiling will enhance flavor. Or, the concoction can be kept in refrigerator.

7. Prepare eggs 2 days prior to serving:

boil eggs;

shell eggs;

add eggs to ginger-vinegar-pig-feet concoction.

8. Take out desired amount of ginger-vinegar-pig-feet-eggs concoction and reheat to serve (room temperature or warm).

SPECIAL NOTE:

1. Cook vinegar in large clay or ceramic pot. Do not use metal “reactive” pots.

2. Prepare vinegar with ginger 3-4 weeks in advance of due date.

3. Add pig feet 1-2 weeks before serving.

4. Add eggs one to two days before serving.

5. Eat daily with meals beginning 12-14 days after giving birth.

6. Prepared dish can be left in clay pot at room temperature and re-boil every week for ginger-vinegar concoction and every 3 days for ginger-vinegar-pig-feet concoction to prevent spoiling.

7. Smaller portion can be taken out from main clay pot and reheat in smaller clay or ceramic pot as needed.

8. Ginger peels were traditionally saved and used to soak new mother’s feet at night to induce a more restful sleep.

Nutritionist Comments

Contributor: Jing Liu, RD

Nutritional Value & Potential Benefits

This dish, in a most economical way, provides most of the balanced nutrition needed by a postpartum woman. Below are some benefits of each ingredient:

1. Ginger – provides fiber for bowel movements, Vitamin C for immune system (1) and reduces inflammation (2).

2. Black sweet vinegar – helps to retain energy and possibly reduces postpartum depression.

3. Pig feet – provides an abundance of calories for milk production and calcium (1) for recovery.

4. Eggs – the most complete protein source for repairing tissues and muscles. (1)

Mindful Modifications

1. If weight gain is a concern, skim off the oil that floats on top of the dish and avoid eating the fatty part of the pig feet, especially its skin.

2. If the dish is too spicy, reduce the ginger, because, according to Traditional Chinese Medicine principles, the ginger may have too much heat properties for one’s body.

Sources

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pork_Knuckles_and_Ginger_Stew

THE CHINESE-AMERICAN POSTPARTUM EXPERIENCE OF THE PAST 170 YEARS

Contributor: Marilyn P. Wong, MD, MPH

The postpartum experience of early Chinese-American new mothers has not been well documented in any historical research although they have been delivering babies in the United States since the 1850's. By following the U.S. immigration policy changes one can deduct some of the circumstances of the birth experience. However, much is unknown.

We pay tributes to the young women pioneers who became new mothers in a foreign land without the traditional support of family and relatives.

1850'S -1870'S

Chinese women who immigrated to the U.S. during this early period were mainly wives of their merchant class husbands. (Few working class men would have the financial means to bring a wife over.) This first generation of women to arrive would not have the benefit of having their mothers or older relatives to help out during the prenatal, the delivery and the postpartum periods. All births during this period of time would be home births. New mothers would most likely follow Chinese postpartum traditions. Few Chinese women at this time would be literate enough to write letters, journals or diaries. There were rare records of such writings to have survived. (To the reader: do you have family stories that may shed light on the postpartum experience of this period of time? Please contact us: m2mpostpartum@gmail.com. We would like to know if there were midwives in the Chinese American community in the 1800's.)

1880'S - 1920'S

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prevented the legal immigration of Chinese workers into the U.S. There would be few Chinese women entering the U.S. at that time except as wives of merchants. They would not have their mothers here in the U.S. There may be a very small number of older Chinese American women who had been in the US for a few decades longer and who could have provided support to the younger women. All births would be home births with some births attended by Caucasian midwives. Chinese Hospital in San Francisco began operation in 1899 to provide much needed medical services to the Chinese American community which was barred from using other hospitals in the City. (When did Chinese Hospital begin to have an obstetric ward? Were there Chinese midwives in the community? Was their service paid? How was Chinese postpartum traditions passed on from mothers to daughters?)

1920'S -1930'S

Given the continuation of the Chinese Exclusion Act, there were few new female Chinese immigrants. Most of the immigrants that came into the U.S. were "paper sons" - people who claimed to be the son of a U.S. citizen to bypass the Exclusion Act. This period of time saw a new breed of Chinese American women - they were born in the U.S., raised in the U.S. and educated in the U.S. They spoke English and saw themselves as American. The fact that they were born in the U.S. meant that their mother would already be here. The new mothers of this era would have the help of their mother. (How did the new mothers of this era view Chinese postpartum traditions? Which traditional practices were observed? Did US-born new mothers of this era believe in Chinese postpartum traditions?)

1940'S -1950'S

More information was known about this period than the earlier time due to the living memories of women in their 80's and 90's. We were incredibly fortunate to have interviewed three women who were able to share their stories. Mrs. Dere and Mrs. Louie’s stories were two sides of the same coin. Mrs. Emma Woo Louie worked as the registered nurse in the maternity ward at Chinese Hospital in 1948. Mrs. Dere gave birth at this hospital in the same year. Mrs. Chan’s story gave details of life in a small town in the Sacramento Delta.

From these three interviews, one can see the transition and the beginning of the disintegration of the traditional mother-to-daughter transmission of postpartum traditions.

We wish to thank the Chinese Historical Society of America in San Francisco who helped in the outreach efforts to reach these women.

Mrs. Emma Woo Louie

Contributor: Marilyn P. Wong, MD, MPH

July 17, 2018

Mrs Emma Woo Louie contacted M2M through email when she received a flyer sent out by the Chinese Historical Society of America seeking Chinese-American women in their 80’s and 90’s for their recollection of postpartum experience. What she was about to share with us was more than a personal story but a slice of history of Chinese Hospital in San Francisco. She was a registered nurse in the maternity ward at the Hospital in 1948.

Chinese Hospital (http://www.chinesehospital-sf.org/history) was built entirely through community efforts in 1899. In the 1800’s and into the 1900’s, Chinese-Americans were barred from using other hospitals in the City. To meet the medical needs of the community, the family associations banded together and raised the funds necessary to build a hospital in San Francisco Chinatown.

--------------------

Mrs. Emma Woo Louie was born at home in Seattle in 1926. Her father was from Saichaak, Toishan (台山) and her mother was born in Guangzhou (廣州) in a family of Manchurian origin. Toishan was one of the main counties in Southern China from which the Chinese international diaspora began. Most of the Chinese Americans (living in the U.S. prior to the 1970’s) as well as Chinese-Cubans and Chinese-Peruvians could trace their ancestral roots to this county. Emma’s maiden name was Woo (胡) and her married name was Louie (雷).

When Mrs. Louie gave birth to her first child in 1949, her mother probably had postpartum dishes made for her. At that time, she did not recall having seen any postpartum recipe written down. She remembered the first Chinese cooking class she attended when she was newly married. It was at the Chinese YWCA in San Francisco and the teacher gave the class some recipes in which the ingredients were listed according to price, not by amounts. For example, a recipe would call for ten cents of onion, fifty cents of pork, etc. This made the recipes obsolete later on.

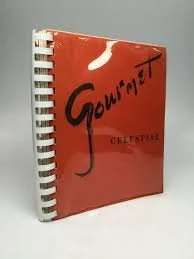

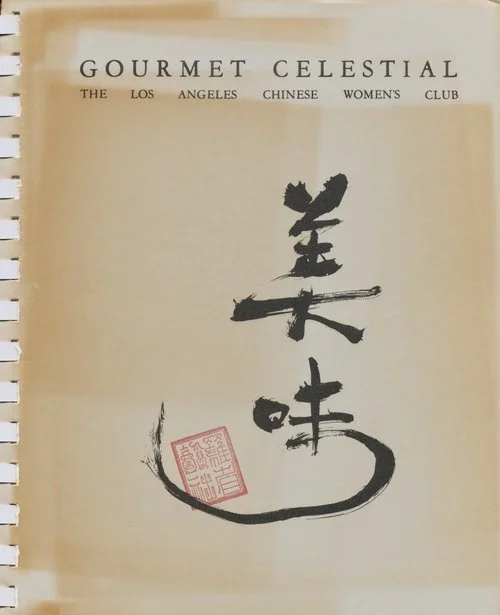

Decades later, Emma did cook the pig feet in vinegar (猪脚姜醋) postpartum dish for her daughter and a daughter-in-law when they gave birth in the late 1980s. She obtained the pig feet recipe from the 1970 Los Angeles Chinese Women's Club cook book, the Gourmet Celestial. Recipes in this cookbook were collected by members of the women's club. The book was edited by Mrs. Tyrus Wong whose husband was the famous Disney artist who created the highly acclaimed visual style of the animation film, Bambi. Mr. Tyrus Wong designed and created the cover as well as the inside chapter pages of the cookbook.

Mrs. Louie remembered fondly her experience as a registered nurse at the Chinese Hospital in 1948. The maternity ward was overflowing with new mothers due to the influx of war brides. Many young Chinese American men joined the U.S. Army and served in WWII. As a result, those who were born in China were allowed to become citizens. Together with the War Bride Act of 1945, some were finally able to return to China and to bring their wives, whom they have not seen for many years, back to the U.S. Other GIs were able to bring back their new brides. (See interview with Mrs. Dere in the section below.)

In Mrs. Louie’s words, “there was a deluge of women, mostly from Toishan, giving birth at the Hospital.” These new mothers were kept in hospital beds for five days to a week. She would break out in laughter as she recalled that many of them would be “tipsy” from eating and from drinking the chicken wine postpartum dish brought to them by family members.

Although the Hospital provided daily meals, relatives would bring Chinese dishes to the new mothers to eat. It was interesting to note that family would bring the chicken wine dish first and then the pig feet in ginger vinegar dish several days later. This was consistent with the teachings in Traditional Chinese Medicine that the pig feet dish was not to be consumed immediately after giving birth.

Many new mothers, following the “fashion” of the time, did not want to breastfeed. Mrs. Louie felt this was due to influence of the upper economic class on those of the lower ones. People thought if babies of the wealthier class were being bottled-fed, then that must be a healthier practice. Consequently, Mrs. Louie remembered, she and a hospital aide, washing and sterilizing many bottles, and preparing formula due to the demand of Chinese American new mothers for bottle-feeding. She thought this created quite a comical scene. These new mothers were being fed chicken wine and pig feet vinegar dishes to promote milk production but, at the same time, were taking medication and were binding their breasts to STOP milk production!

Another comical scene flashed in Mrs. Louie’s mind as her thoughts were transported back to 1948: accreditation of Chinese Hospital. The Director of Nursing was a Caucasian woman who served in that capacity for many years. She lived on the top floor of the hospital. Mrs. Louie recalled being told that the State is sending someone to inspect Chinese Hospital for accreditation. The overflow of babies in the nursery had to be moved out because of state regulations that limited the number of infants according to room size.

The only room available was the one private room on the maternity floor. So the new mother in the room was temporarily moved to the surgical ward and two drawers were taken from a bureau and placed on the bed. Three babies were placed in one drawer, three in another; each infant separated by rolled-up towels. The room was also set up as a proper nursery. And a sign that said “Do Not Disturb” was placed on the door. Mrs. Louie was given instruction to “make sure none of the babies cry” when the state inspectors came. Her reply was that “Chinese babies do not cry.” And they didn’t! With that, Chinese Hospital was re-accredited in 1948.

--------------------

Mrs. Dere

Contributor: Marilyn P. Wong, MD, MPH and Jean Dere

6/27/2018

Fremont, California

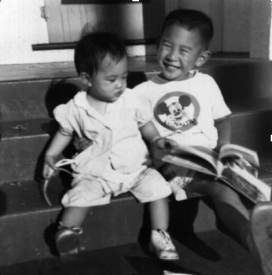

Photos: (L) Mrs. Dere with eldest son on rooftop in SF Chinatown, 1949; (R) at the same location 1952

Mrs. Dere was one of the first women I met after I immigrated to San Francisco from Hong Kong at the age of 11. Her family lived on the second floor and our family lived on the first floor of a set of three flats on Powell Street adjacent to Francisco Jr. High School.

She is now 92 years old. I recently visited her at Aegis Garden in Fremont, an assisted living facility catering to Chinese American seniors. The staff members were all Chinese-speaking and the food was cooked for a Chinese palate.

Mrs. Dere was born in 1925 in Hin Gong Village, Hoi Ping District of Guangdong, China. She came to the U.S. in 1948 after marrying Mr. Dere who had returned to China to take a bride. Since being in the U.S., Mrs Dere had been a housewife, a seamstress and a key punch operator.

Mr. Dere had been in the U.S. for many years before joining the US Army during WWII. The US and China were allies in this war and this relationship led to some major changes in policy toward the Chinese living in the United States. This war ended 60 years of U.S. immigration exclusion against the Chinese. Chinese American citizens who served in the US military during the war were allowed to return to China to marry and bring their wives to the US with the War Brides Act of 1945. Almost six thousand women were brought into the US as a result. Prior to the end of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, most Chinese American men lived a life of virtual bachelorhood. Those who were able to save enough money to return to China to take a wife would often only be able to visit their wives a few times over several decades..

Mrs. Dere was the youngest of six children. Her two older brothers were more than 20 years her senior and both were in the US along with their father. She was born after her father retired and returned to China permanently. Consequently, she was raised by one of her sisters-in-law who had a daughter of about the same age. Mrs. Dere’s own mother was in poor health. She remembered being a refugee (走難) together with her fourth older brother and dodging the advancement of the Japanese military occupation in China. As a result, her formal education was disrupted.

When the war ended, Mr. Dere, like thousands of other Chinese American young men, went back to China seeking a wife. Word soon spread and he was introduced to Mrs. Dere. They were married shortly after they met. Mr. Dere brought his new bride to the U.S. in 1948 when she was 22 years old and pregnant with their first child.

They arrived in San Francisco in March of 1948. Their eldest son was born in August of that year. Subsequently, she had one child every August for the next two years and then 3 more children over the course of the next 10 years.

All the children were born at the Chinese Hospital. Her husband did not attend any of the births. She remembered that the nurses were Chinese and the food was brought from home. Among the dishes were chicken with wine and ginger vinegar with pig feet and eggs. The hospital stay would usually last about 3 days. With her first three children’s birth, she did not have any help from family members during the postpartum period. She had to manage the household, the newborn baby and her older children by herself until her mother-in-law was able to immigrate from China near the end of 1951.

This was in contrast to the postpartum experience that she saw in the villages of China. There, older women in the village would be attending the births and relatives would be around to help the new mothers.

She adhered to most of the Chinese traditions such as not leaving the house or washing her hair for 30 days. She did not believe that all new mothers followed these traditions - “only if they wanted to”.

Some of the women at that time would give birth at home. Mrs. Dere suggested that this may be due to financial constraints. It would have been more expensive to have a hospital birth than a home birth. She was unsure if there were midwives to attend the home births. Most of the people that she knew had hospital births.

This was her recollection of giving births in San Francisco Chinatown in the 1940’s and 1950’s.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Mrs. May (Tom) Chan

Contributors: Marilyn P. Wong, MD, MPH and Ron Chan

9/15/2018

San Leandro, California

Photos: (L)1948 and (R) 2000

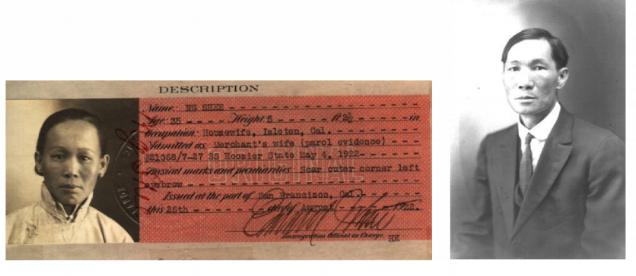

Mrs. May (Tom) Chan was born in Isleton, California, in 1928. Isleton was a small town in the Sacramento delta area, 10 miles from the more well-known Chinese-American town of Locke.

May’s parents immigrated to the U.S. from Chung Shan County (中 山), Guangdong Province in 1910. This county from the southern part of China was the ancestral home to many Chinese immigrants in the United States. Mar Shee Tong (father) and Ng Koon Lan (mother) settled in Isleton at the time of its incorporation as a city in 1923. She remembers Isleton as having three distinct districts: European, Chinese and Japanese.

Photos: (L) Ng Koon Lan, May’s mother (1922) and (R) Mar Shee Tong, May’s father (1926)

May’s mother gave birth to eight children. Three were born in China, one died at birth, one infant child died on Angel Island while May’s mother was waiting for her immigration interrogation. Five were born in Isleton, California, with four surviving. They were all home births.

Her home was located at 18 Main Street, Isleton, and it still stands today. The family was a tight-knit unit. May would repeat often that her family was poor but rich in happiness. Her father (Mar Shee Tong) worked as a cook in the gambling house in Isleton.

The family would sustain on vegetables grown in the backyard and left-over scraps from the gambling house. In time of extreme difficulties, she remembered her lunch would be pieces of bread with a sprinkle of sugar. Or dinner consisting of hot water with crackers crumpled in. She also learned to suck cooked rice in her mouth for 10-15 minutes until the carbohydrate turned into sugar – that was her “candy” treat.

May was the last of eight, and a daughter. In Chinese culture she held very little status. When she was very young, she was given away to a childless Chinese American family who lived across the street. It was hard to feed so many hungry mouths. However, when her father came home and found out what had transpired, he told May’s mother to bring her home immediately - “this family will live as a family or die as a family”.

Some of her earliest memories were of her interaction outside of the Isleton Chinese American community. For example, she remembered that her first encounter with “Santa Claus” in kindergarten was a frightening experience. Seeing a head full of white hair and white beard on a white face was a scary sight for a 5-year-old May.

She also remembered the disparities in the condition of the two elementary schools in Isleton. The one attended by European American children was built of bricks and had manicured lawns. The “Oriental School” for the Chinese American and Japanese American children was simple and had a dirt playground. Elementary and middle schools were segregated. All the students from the two segregated middle schools would be mixed when they entered high school at Rio Vista. May felt that she had to adjust to the desegregated environment.

During her high school years, WWII broke out. Adult males of draft age were called to serve in the military. Two of her brothers were drafted. Consequently, there was a shortage of laborers in the agricultural fields. Women and young people were called to fill the void. May worked as a tomato picker, earning 50 cents for every crate of tomatoes picked. It was hard work but the money came in handy. Black soldiers from Pittsburg, California, also worked in the cannery. May, who weighed less than 100 pounds, was helped by these soldiers who told her that, “you’re too little to lift those heavy crates”.

When she turned 17, she worked in the cannery – the National Cannery Company – first sorting tomatoes, then she was promoted to canning and then to working in the warehouse. Her brothers, sister and mother also worked in the cannery in the sweltering summer heat of the Sacramento Delta. She had also worked in picking asparagus in the freezing fields.

May was living at home during this time. When she was 18 her sister, Connie, returned home with her young daughter after her divorce. Mrs. Chan had to move out to Sacramento where she started working in the DMV as a key punch operator. She met her husband, Alfred Chan, in Sacramento and was married at the age of 22. At the time, Al was working in a supermarket while attending college.

Photos: (L) Alfred and May at their wedding banquet in 1950; (R) their children Ron and Melanie in 1958

After their marriage, they moved to Oakland where they continued to live for the next 68 years. They had a son and a daughter. Both were born at Peralta Hospital in the mid 1950’s. By this time, most births were hospital births. She did not recall following Chinese postpartum traditions except she was given a bowl of chicken wine soup several weeks after her delivery. Her mother-in-law cooked it for her and she felt obliged to drink it. Within hours of drinking the soup, she began to hemorrhage. She had to call her doctor, Dr. Yee, to make a home visit. The hemorrhage stopped a few hours after the doctor’s visit. But, to this day, she felt the soup likely precipitated the hemorrhage. Her sister, Connie, stayed with her for the entire month to nurse her back to health.

2010'S

CAUGHT BETWEEN MY MOM AND MY OB

Contributor: Tina Yeung

3/30/2018

New York City, New York

(Photos: (L) me and my daughter, Kaia in 2017; (R) my mom and me when I was a baby)

(Tina was asked to write about her experience as a new mom in the 21 Century. With changes in U.S. immigration policy in the 1960's and 1980's, there has been an influx of immigrants in family units. Tina grew up in the United States with her parents who immigrated here from China as adults. Tina's experience is typical of second generation Chinese Americans who grew up in a bi-cultural family. Tina shared her postpartum experience and contrasted what her mother expounded and what her obstetrician recommended.)

So here are some differences between what my OB and my mom suggested for postpartum care:

-Immediately after my unplanned c-section, doctors put me on an all-liquid diet until I passed gas to prevent vomiting. My parents came to the hospital with bags of homemade soups, noodles, and eggs. They were bewildered that the doctor wouldn’t let me eat because I needed to “eat to regain [my] energy.” As a balance, I drank the soup, but I had to fight my mom the entire time while she tried to force feed me noodles. (To be honest, though, I was very hungry and the oily chicken soup was very comforting.) When I did finally pass gas, my mom cooked almost 7 meals a day for me. Many of the foods were dishes I had grown up with and loved, so I did not complain. I’m sure doctors would’ve recommended a more balanced and lighter postpartum diet though.

-My mom did not allow me to shower/wash my hair for at least two weeks postpartum. I didn’t think I could last that long, so I secretly showered at the hospital before leaving and once when my mom went out.

-My mom consulted many relatives and Chinese doctors for postpartum recovery herbal medicine, some to replenish blood and others to strengthen my spine/muscles. I had no idea what was in the herbal soups, but I drank it all (I lost that fight). She also made a lot fish maw (swim bladder of fish) because of the nutrients. I did some research and found that fish maw is considered to be high in protein and low in fat. Although I didn’t think it was as nutritious as my mom suggested, I also didn’t see any harm in it, so I mostly ate it without protest.

-Doctors recommended going on frequent walks to prevent blood clotting. My mother ushered me to bed every time I stepped out of my room because I “needed to rest.” She even wanted me to eat in bed. I wasn’t allowed to expend any energy for fear of chronic pain later on. I protested and was allowed out of my room to eat in the kitchen, but my mom insisted I go back to my bed afterwards. I eventually snuck out for a few walks, but I have to admit, I grew very tired and my wound was sore just from going around the block.

-Doctors also recommended fresh air. Because I had my baby in the winter, my mom worried that I would catch a chill if I sat near the window or didn’t have socks on. Similarly, I wasn’t allowed to drink anything that was not hot. Nick once poured me a glass of water from the fridge, and my mom literally jumped out of her chair to stop him.

-Skin-to-skin was a concept that completely eluded my mom. Every time I did skin-to-skin with the baby, my mom, fearing that we would catch a chill, draped a thick blanket over us, and proceeded to grieve about how ridiculous it was.

-Along with skin-to-skin, my mom also did not understand why I needed to nurse the baby as frequently as I did (every 1.5-2 hours around the clock). For my sake, she suggested we supplement with formula at night, so I can rest. I persevered to exclusively breastfeed but spent many evenings expressing to my mom the importance of my decision.

All in all, my month of confinement involved a lot of protesting, both from my mother and me. We had to compromise and negotiated frequently on topics around food and coddling. I believed in the evidence-based practices that my doctors recommended, but at the same time, these traditions have served Chinese women well for over 2000 years. I followed some of the rules and broke many. It was a tough month, but I know I would’ve over exerted myself had my mom not been here to force feed me and usher me back to bed.